As people-powered campaigning is clearly a practice on the rise, largely inspired by the dramatic rise of progressive grassroots movements, we often hear NGOs asking for more clarity on what kind of model would work best for them.

Though self-arising, often youth-led movements around climate and social justice are certainly inspiring, the organizing models they employ pose challenges for larger and older organizations, who are often concerned with maintaining stable and sustainable programs over time.

This is not to say that people-powered campaigning can’t do great things for all types of organizations when deployed properly. It’s just that established organizations generally have more success with a structured, distributed organizing approach as opposed to a horizontal and self-arising decentralized one.

So here is a bit of clarification of terms that may help.

Decentralized organizing

Decentralized organizing most accurately describes the emergence of self-arising groups, usually sparked by a social change flashpoint. Here, a common frame or understanding around the need to act motivates local organizers to start and lead groups with total autonomy. These local groups, however, do share some connectivity with each other, facilitated through digital technologies, as well as a sense of common purpose and a common philosophy. However, they are not usually bound to work together or align on strategy and tactics. Examples of decentralized organizing include the rise of over 900 Occupy Wall Street camps across the world in 2011-2012, the early forms of both the Movement for Black Lives, (Black Lives Matter) the Indivisible Network, and more recently, Extinction Rebellion.

While the decentralized model can scale in dramatic ways and attracts the attention of many thinkers in advocacy organizing, it is a model that has limited use for structured organizations that seek to build power and manage networks over the long term. The very horizontal nature of truly decentralized movements is part of what attracts wider participation and leadership but also makes the overall network hard to maintain and coordinate without very active effort throughout the nodes of the system. In fact, the radical autonomy of local groups within movements such as Occupy, according to Rutgers Professor Todd Wolfson, was among the significant factors that led to the eventual fadeout of the network[1].

Distributed organizing

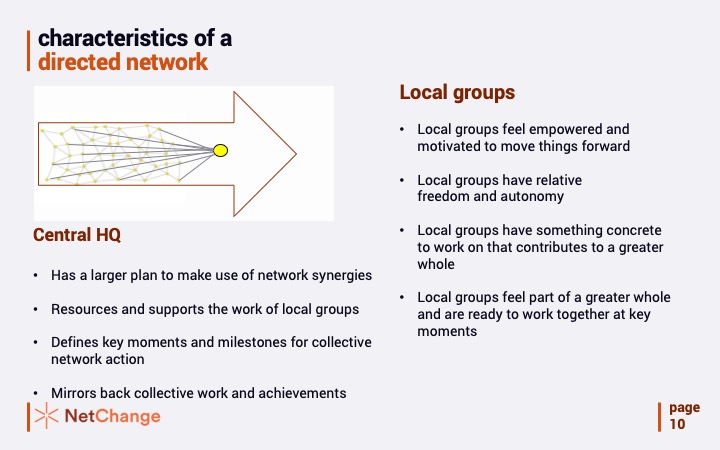

In its common usage, distributed organizing is used to describe an approach that also allows for a degree of autonomy and local leadership around a common cause but is designed as a more centrally-directed system, where the catalyzing organization defines the framing and overall strategy for the network and local groups or individuals are free to take on and manage their own actions within this framework. In a distributed organizing system, all local groups are in touch with the central organizing body and often connected with each other through planned convenings and coordination events.

While distributed organizing can be set up in several different ways and with varying degrees of local autonomy, the model we have identified as being common to the most successful advocacy approaches in our 2016 Networked Change Report was one we called “directed-network campaigning”. In this approach, organizations take the lead in defining strategy and the overall shape of actions needing to be deployed but leave their supporter networks with significant freedom to innovate, manage and customize at the local level. This activates larger segments of the population that are willing to add their energy and initiative to an effort, without the responsibilities of thinking up the strategy and tactics on their own.

Organizations launching and managing distributed organizing systems establish the overall framing of the campaign in such a way that active supporter participation and leadership is an essential part of the program. Typically, they also share the overall strategic plan with supporters and outline the role that people power will play in achieving shared goals.

As

initiators of a larger network of supporter-driven actions, catalyzing

organizations establish overall process design, which includes thinking through

supporter path and roles, establishing a recruitment and onboarding process as

well as setting up coaching and support systems for supporters.

Being both facilitators and in a sense, conductors of this distributed network, catalyzing organizations define the key moments of collective action and also direct their supporters towards shared milestones. Leaders in this field also spend time mirroring back the results of collective efforts to validate the worth of individual contributions and leadership and to show the impact of the network, which are essential practices for maintaining morale and motivation, since these networks run largely on donated time and energy.

In future posts we will discuss why and how a large number of advocacy orgs are turning to distributed organizing in new campaigns.

**Featured image is a RAND Corporation illustration of different possible network forms in the 1960s, theoretical models that eventually determined the architecture of the World Wide Web.

[1] Wolfson, Todd. Digital Rebellion: The Birth of the Cyber Left, Illinois, U.S., University of Illinois Press, 2014.