If you’ve still got too much “old” power driving your institution, here’s something to share with your boss, board and management team. New Power, by Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms is just the thing to create a stronger sense of urgency and alignment towards updating your model.

And while I’m not the world’s biggest fan of Purpose, Heimans’ flashy NY agency (because I don’t believe “insert $500,000 for an insta-movement” actually works, I don’t love when people sell insights learned in progressive organizing to anyone with a check, and I’m suspicious of the value big agencies with fancy offices in global cities really offer) the truth is these two have honed the New Power story over years and have direct experience tapping and implementing it. They really are are excellent messengers for people who established their management or campaigning mindset before the web took over (they even got David Brooks to talk about social movements!).

My good friend and PDF / Civic Hall co-founder Micah Sifry wrote a great review of their book and has given me permission to repost it here.

New power and the dynamics of digital change (by Micah Sifry)

If you are looking for a fresh and comprehensive analysis of how the Digital Age is transforming the civic arena, get yourself a copy of New Power, Jeremy Heimans and Henry Timms’ new book, which is being released today. It’s based on their 2014 article in the Harvard Business Review, which made a simple and compelling case for the rise of new power:

Now they’ve expanded that argument into a book, filled with examples ranging from Pope Francis to the Ice Bucket Challenge, Lego to ISIS. As guides to the changing playing field, Heimans and Timms aren’t mere observers. Heimans cut his digital organizing teeth helping launch the Get Up Australia e-group, a story he recounts in some detail in the book, and later helped create the global digital lobbying force Avaaz. And as founder of the consulting firm Purpose, he’s been a seminal force behind a wide range of projects, incubating projects like the global gay rights group All Out, the pro-refugee Syria Campaign, and the civic tech hub Meu Rio, and crafting strategy for efforts like Everytown and the ACLU’s People Power campaign. And as director of New York City’s 92nd St Y, Timms founded #GivingTuesday, an open source answer to the hyper-commercialism of BlackFriday and CyberMonday. As I’ve written elsewhere, #GivingTuesday has become the most successful civic tech culture hack of the decade, unleashing hundreds of millions in donations to thousands of nonprofits worldwide.

Full disclosure: I’ve known both Heimans and Timms for years and consider them friends and fellow travelers. So, this isn’t an unbiased review.

What I found most valuable about New Power was the effort Heimans and Timms made to flesh out the backstory to many of the new power moments they use to enliven their larger argument. For example, they lucidly explain the origins and early organizing efforts of the group Invisible Children before they take us through its explosive flameout with the Kony 2012 video. I’ve long used that case as an example of how hard it is to convert momentary global fame into ongoing on-the-ground action in our age of hyper-distracting media, but in Heimans and Timms’ hands Invisible Children is first and foremost a great model for how to build what they call a “new power community.” That’s a place where three key factors are aligned: a platform owner who stewards the community’s brand and purpose, an engaged group of “super-participants” who do a lot of the heavy-lifting and gain meaning from being able to help shape the community, and a larger base of regular participants who come along for the ride.

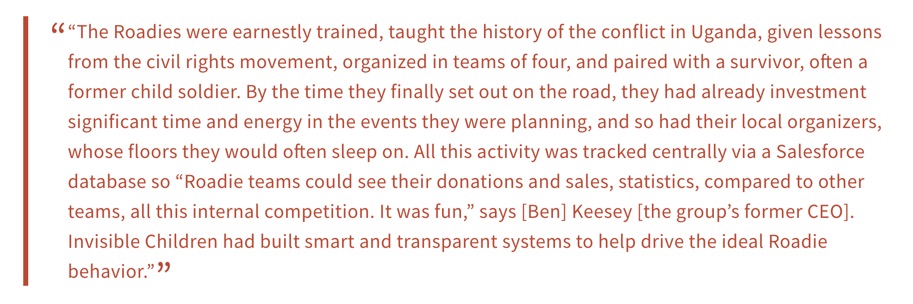

In the case of Invisible Children, which was founded to stop the recruitment of child soldiers into Kony’s militia in Uganda, the super-participants were called “Roadies,” young people who would pledge six months of their lives to do field organizing for the organization. Using screenings of documentary-style videos as their draw, Roadies would travel to mostly Christian colleges spreading the word. Heimans and Timms report that “in total, they launched 16 tours, leading to over 13,000 screenings that reached an extraordinary 5 million people.”

This work helps explain why the Kony 2012 video took off so explosively when it was first released, reaching 36 million YouTube views in two days. It wasn’t just the social media seeding that happened through tweeting at celebrities to share it; Invisible Children had built a real distributed base with a lot of local effort. But the huge success of Kony 2012 literally blew up Invisible Children’s carefully constructed community. Suddenly, millions of people were encountering the group solely through the video, which positioned its founder Jason Russell as some kind of charismatic super-hero divorced from the people who had helped build the organization with him. The wider world didn’t know Russell as the lovable rogue who had built this project out of personal passion; and specialists on the topic of child soldiers didn’t know him or his organization, and they didn’t care for the “white savior complex” he exemplified. The backlash was fierce and within days Russell suffered a very public mental breakdown, while the Roadies, IC’s super-participants, were “left feeling confused and disempowered.” For Heimans and Timms, the Invisible Children debacle shows what can happen when a new power community loses its internal alignment.

The centerpiece of the book is a four-part grid that the authors call the New Power Compass (see below). At one end, embodying the old power model and value, are what they call “castles” like the IRS and the Encyclopedia Britannica. (Heimans and Timms should really have given credit for this concept to Beth Kanter and Allison Fine, who first popularized the metaphor of legacy organizations operating as castles in their seminal book The Networked Nonprofit.) On the other end of the grid are “crowds” embodying new power models and values like #BlackLivesMatter and Wikipedia. Old organizations with new values are cheerleaders, while new organizations with old values are co-opters. It’s nice to see that the authors situate Facebook next to Uber as an entity seeking to harvest the value created by a crowd rather than truly empower it.

Regular readers of Civicist will appreciate that New Power pays attention to some of the edgier and more innovative models of change that are out there, and not just the successful political and corporate campaigns that make up the heart of the book. The authors report on the rise of Podemos in Spain as a new power phenomenon, with perhaps a bit too much of a rosy view of that movement’s centralized leadership. And they also cover the digital democracy movement being stewarded in Taiwan by the likes of Audrey Tang, the rise of the platform cooperatives movement, and efforts like Holland’s De Correspondent to build a citizen-driven journalism platform.

My only criticism of New Power, which I hesitate to make because the birth of a book written by friends is mainly a cause for celebration akin to the birth of a child, is that it is too optimistic about the world it aims to explain. Written primarily during what we should now probably call the “second tech bubble” of the Obama years, New Power doesn’t say enough about the dark sides of the Digital Age: the immense wealth it has concentrated in the hands of a few, the intense violations of privacy, the heightened power to manipulate crowds with disinformation.

To be sure, there is a moment they critically recount from a Davos conference panel that imagined crowdfunding basic public services, as if we could recreate government and taxes via Kickstarter. And they adroitly dissect Donald Trump’s powers as a “platform strongman” taking advantage of the emotional susceptibility of crowds. But while I came away from New Power better informed at how campaigners and organizers can surf digital waves to victory, I was left still wanting to know if Heimans and Timms believe new power is actually shifting the balance of power to people who have historically had less, or just reshuffling the deck into the hands of some new bosses. Same as the old boss?

This review was posted with permission from the author, the incredible Micah Sifry. We encourage you to follow Micah on twitter, subscribe to his excellent daily newsletter Civicist First Post, or stop by their beautiful shared office and event space in Manhattan, Civic Hall.